Archive for the ‘Songwriting’ Category

Over the weekend I gave a short, dense talk (no slides), for CMU’s DIY strand at The Great Escape Convention. I looked at first steps to recording for new music artists. This isn’t a transcript but here are the key points, from my notes. By necessity it’s a bit topline for the target audience but I hope it’s useful…

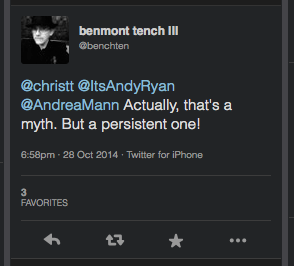

For years, one of my favourite songwriting anecdotes has been this story, about Fergal Sharkey’s two big 1980s hits. It goes like this: Sharkey’s massive solo smash ‘A Good Heart’ was written by Maria McKee (legendary Lone Justice singer and solo star) about Benmont Tench (equally legendary genius keys man in Tom Petty’s Heartbreakers). Then Sharkey’s follow-up hit, ‘You Little Thief’ was written by Tench in response to McKee, so Sharkey turned into smash hits these two songs that are actually a conversation.

I love that anecdote, I re-tell it whenever any of those people gets even the briefest mention. There’s magic in two passionate, both lyrically superbly crafted songs, attacking the depth and detail of a clearly doomed love affair from different angles, then the material getting discovered and ‘curated’ into the pair they’re meant to be, by an entirely different artist.

Sometimes I add Deacon Blue into the mix, who wrote ‘Real Gone Kid’ about McKee, making her the muse of two very different classic 1980s hits.

Anyway, sadly the other night I discovered it’s a myth. I retold it to a friend on Twitter when she mentioned ‘A Good Heart’ and – yes you know where this is going, only in social media – Mr Tench himself popped into the conversation to debunk the myth. He did write ‘You Little Thief’, it’s just (he’s saying) it’s not about Maria McKee. He didn’t explain whether McKee’s ‘A Good Heart’ is about him – but then he’s probably the wrong person to ask about that.

Twitter, eh. It was well gutting that the story isn’t true. At the same time it was well ace to get it from the horse’s mouth, especially from a guy who has informed my whole life as a keyboard player, on a par with Bittan and Federici. I didn’t make it up, by the way, it’s the ‘established version’. I was tempted to reply “but it’s on Wikipedia, it’s MUST be true,” to the actual person who’d know.

Twitter, eh. It was well gutting that the story isn’t true. At the same time it was well ace to get it from the horse’s mouth, especially from a guy who has informed my whole life as a keyboard player, on a par with Bittan and Federici. I didn’t make it up, by the way, it’s the ‘established version’. I was tempted to reply “but it’s on Wikipedia, it’s MUST be true,” to the actual person who’d know.

Anyway, that only leaves Evan Dando’s ‘It’s About Time’ versus Julianna Hatfield’s ‘For The Birds’, where he’s trying to persuade her to have sex with him. I hope that pairing doesn’t get debunked but if it does, I hope it’s Julianna who tweets in.

Right so ‘Bury Me With A Scarab’ is the second single taken from The Bear and it’s out now. Here are the lyrics and at the bottom I’ve written about them, in some fashion…

When you’re a support act, your gig isn’t a ‘show’ in the complete, arching way a headline is; the job is vaguely to set up the crowd from cold-ish, while trying to make friends with an alien audience (though I’ve had an optimistic, heartwarming number of mates and fans at these gigs). So on one hand, you’re freed to experiment, challenge yourself (especially when it’s just one tour in many), yet on the other hand you have a more complex bunch of responsibilities towards people who don’t know you.

The tour I’m finishing now (opening for Emily Barker & The Red Clay Halo) has an older, more folk-literate (and small-c conservative) audience than mine, with a range of ages (some gigs are 18+, some full of families). It’s a healthy challenge that has almost entirely been excellent fun and (I emphasise) a large number of hugely inspiring gigs to many lovely people. But this isn’t a blog about that, this is about the night that went very odd for me, perhaps even badly awry. In Cambridge, of all places.

The 40 minute setlist I kicked off the tour with, driving around north Scotland, back at the start (feels like months ago but was early October), was too lightweight and warm; almost no politics and just one or two darker songs – and only one on piano. It was heavy on the A.A. Milne poems in the first half, to put people at ease but this wasn’t quite right, so after we came down from Scotland, after we’d done Brighton (getting my hometown show out of the way, which is different anyway) and arrived at Shepherds Bush Empire, I shook it up: dropped a Milne poem, switched to a more challenging, downbeat opener – doing Tunguska on piano. This made room for a second piano song later on and, best of all, I realised I could trust Emily’s audience to get a lot out of Tall Woman (from Love Is Not Rescue) on piano.

So from then – and for a while – I felt I’d established a set that worked for these shows and the Red Clay Halo audience, with light and shade but not too many T-T extremes.

However there’s something tricky about all this and it’s definitely thrown me off: not quite being a ‘real me’ onstage. Maybe the prioritising of people who know me less, above those fewer people who really know my stuff, or maybe just a limit on the pure truth when compacted into 40 minutes. But however pretentiously I frame it, what happened was, as the tour rolled on, I caught myself stretching out jokes and dicking around between songs, even to the point of dropping a song to leave more room for stupid interaction. This has happened a few times before and it’s become a warning sign (for example near the end of my tour with Franz Nicolay back in 2011) – that something is up somewhere in the music itself.

Then came a late night tour bus conversation that totally threw me. I got challenged about under-selling the material, about the opaque nature of my songs, in contrast to this ‘open’ character singing them. Also, a couple of live reviews have seemed to ‘write down’ the quality of songs, with a hint that I’m ‘enjoying myself’ too much, perhaps just along for the laugh. We’re mainly getting reviewed by (largely amateur) folk scene bloggers who’ve never heard my stuff and I wonder if the ‘taster’ support set is simply too far outside their comfort zone.

Anyway, whatever the reasons, as we arrived in Cambridge I (almost automatically) made a decision (set firm rules) to perform without fun (!), to drop any Milne, pick as dark and weighty a setlist as humanly possible and see if I could find a route through the set without a single compromise to personality. To not smother any fragility.

With hindsight, writing it down, it’s fucking bonkers: definitely self-destructive, though in the hours leading up to the show, I felt almost deliriously liberated by this plan. The result (of course) was hugely pessimistic: a bleak-as-shit song selection and performance. Through the middle, probably the bleakest run of songs I’ve ever done, especially without introducing them or lightening the tone in between. Ankles is particularly tough on an older, crowd (with more powerful taboos in place about domestic violence) and I did it as slowly and quietly as I ever have, without a warning or explanation. It got a couple of walkouts and three people also mentioned on the merchandise that it was too much for them.

I do believe the audience was appreciating the music (confirmed by friends I had there – who also texted later to check I was OK!). But (no surprise) the crowd certainly didn’t “like” me personally in the way they might at a normal show. So I wonder about this: I wonder about artists who are enjoyed for their perceived vulnerability and what that gives them, sharing it onstage, Elliott Smith, John Mury, bloke from Brian Jonestown Massacre. It was possibly a taste of being that character – but not so empathic – since that’s no more my true persona than the over-cheerful one on previous nights.

Oh, for the socially disastrous nature of performative personality. What it felt most like was people came to see Emily Barker & The Red Clay Halo and first had to sit through a punch in the stomach – which is definitely, 100% the wrong way to approach a support set!

In my case, the most immediate result was almost no-one (I didn’t already know) approached me on the merch stall*, so I sold far, few fewer CDs than any other night and I was punished in the pocket. Fair play!

There was a big positive outcome: every live set since has felt like much closer to the correct balance between authentic (non-schtick) dicking around and the serious moments within the songs. Fundamentally, it solved the original problem – but at the cost of a show. I simply have no idea how I could’ve fixed that trouble without screwing up one gig.

Sometimes I think this whole game is about looking for yourself onstage, your true self, in parallel to the difference between loving song and just loving the idea of song.

*totally unrelated but it’s fun that WordPress auto-corrects ‘merch stall’ to ‘mercy stall’. Apt name!

LYRICS: THE BEAR

Shit in the woods! Our first single (and title track) from the new album is ‘The Bear’. Since the lyric video went online I’ve had a pile of people ask me to explain the song, which seems like a reasonable request but each time I try, I quickly get stuck. As I sing in it; “I don’t even understand what I wrote to myself.” So do I even know what the flip I’m singing about?

LYRICS: Idris Lung

The first taste of our new LP is the song ‘Idris Lung’ because it’s included on the new Xtra Mile label comp Great Hangs. Here’s the lyric and at the bottom a bit of an explanation.

‘Idris Lung’ by Chris T-T

Breathe in smoke through the Idris lung

Nothing we say can ever be undone

You stare at a face you will end up hating

Gutless transparent and asphyxiating.

Sitting in a circle the angels came

They slowed down time, they stole your name

Colours in the sky: shame and fear

You’re so fucking high it’s crystal clear:

You wanna be an atheist but you’re not

You don’t wanna believe but it won’t fuck off

Breathing smoke through the Idris lung

Nothing we say can ever be undone.

We disarm your defences

We’re in command of your senses

You’re Michael Caine in Children Of Men

You were cool for a while but you died in the end

We’re watching television with a gallon of wine

And we make all our money playing cards online

Yours was the face that you ended up hating

Gutless, transparent and out-of-breath

But we’re breathing smoke through the Idris lung

And we’re not giving up til there’s nobody left

We’re not giving up til there’s nobody left

We’re not giving up til there’s nobody left.

This lyric is about a moment of clarity that only comes when you’re very stoned. An ‘Idris lung’ is a lung (for inhaling pot) made out of an Idris brand 2 litre plastic fizzy drinks bottle. Magoo used to make them all the time. Back in 1996 I wrote a song with the same first two couplets and keyboard riff – it was my first 7″ single in 1997 but I haven’t been able to refer back to it (was a 4 track home recording) because I can’t listen to the vinyl, so I have no idea how similar or different this sounds. It’s very much a new song at heart, though: it was mostly inspired by being high in a motel room in Joshua Tree a few years ago and looking in a mirror and seeing what I look like to others, for maybe the only time ever, which was a CRAZY (wildly odd, horrific) moment that I’ve never forgotten.

Unusually, I’ve had no feedback about what people think of it, maybe because musically it’s (deliberately) a curveball / dislocating first taste for a new T-T album, very different from what people may have heard before. Maybe people hate it and that wouldn’t necessarily be a bad thing. I love the collective vocal (Hoodrats sing the whole song not just me) and I love the beats-heavy ness of it. I love the sense in which the collective voice of the universe slaps down the individual narrator, at his most vulnerable, high as a kite. Also Jon Clayton’s keyboard effects solo after the explosive bit is immense. It makes me think a tiny bit of ‘Flame’ by Sebadoh. Sorry about the Children Of Men spoiler by the way – but that’s an old enough, great enough film that you should’ve seen it by now.

A couple of people have pointed out that calling the new album The Bear when it’s so dark / sweary / alt-rock could be funny for listeners who’ve only discovered me through the A.A. Milne stuff. Let’s embrace that potential as a great one!

So, I’ve not yet had a single response – and even the band were a bit iffy about ‘Idris Lung’ because we constructed it, rather than us playing it live like so much of the new album, so I hope people are as bemused as I think they are, rather than just hating it on first listen.

This article was originally published in Louder Than War magazine.

A great number of UK music artists I admire now use crowd-funding platforms like PledgeMusic or Indiegogo to raise cash from fans, to fund albums, videos, or touring. It’s very quickly been normalised in the music industry, to the point that you’ll almost never hear a bad word spoken about these platforms. Unusually, they’re popular with mainstream upcoming artists, the companies around them and also fully independent, self-described DIY or underground artists.

But something in me finds them disconcerting. I admit I’ve not once contributed money to an artist’s Pledge campaign. Each time I hear about one, even when I adore the artist, my heart sinks. Yet people clearly feel it works and there are a pile of happy (on the surface at least) customers. It’s a perfectly legitimate way to fund music in the new online paradigm.

So, what’s my beef?

As hugely successful US crowd-funding company Kickstarter launches in the UK; for the first time offering a serious competitor to PledgeMusic, it’s worth considering the case against, if only to enable a debate when the narrative is so blandly positive. Full disclosure: I’ve never tried it myself. Xtra Mile Recordings did run a successful Pledge campaign to replace stock (including my albums) destroyed in the depot fire (after the London riots) but I have no personal experience of running one. Trying to figure out why I’m not into them, here’s what I’ve come up with:

The emperor’s new clothes. Wasn’t half the point of going online to get rid of third parties? Instead it’s a messy battle. We binned major labels but got trapped in the price-controlled, tax dodging chaos of Amazon and iTunes, even when Bandcamp gave us a cleaner alternative. Then along came this whole new generation of third parties, jumping in ahead of the distributors to get their share, before the music’s even made. And because the process is automated, artists and punters alike seem blind to an obvious truth; at a basic fundamental level, web-based platforms are the same old villains wearing a hipper jacket. Yet again they find a thing that artists (wrongly) believe they can’t do alone, then slide in between artist and audience by offering that thing as a service, in order to cream off profit.

I’m convinced almost any artist with a moderate fan-base can crowd-fund just as easily, with less commitment, more control and a greater overall ROI (return on investment), just by having conversations with the right people. What is it about these formal frameworks that let the artist off the hook of asking personally for support, when it’s usually the exact same people who end up contributing anyway? You want someone’s money, fucking go and ask them. Write a letter. It feels as if everyone’s playing at grown-ups by using a third party website as a dressing-up box.

That’s too much money. For running a largely passive, artist-driven web-based platform (nothing more complex than Flickr, Instagram, Facebook or a hundred other free sites) with a simple financial processing structure bolted on, these companies charge 15% of revenue – and are less than transparent to funders, who are often only vaguely aware that there’s a percentage taken at all. And that’s a lot. That’s what a music manager or booking agent took in the old days, for doing a massive load of work to bring in income. Artists have spent 100 years deeply resenting – and regularly sacking or suing – managers and agents on the same percentage they now happily give to strangers for letting them sit on their web servers for a bit.

Treats for funders are embarrassing and a total arsehole to get done. Money is teased out of devoted fans with offers of rewards, exclusive content, private attention, all sorts. But these bring the wrong kind of closeness; too big a sense of a personal debt owed; often placing artists in uncomfortable situations. Trying to record music with 25 funders sitting in the control room as part of a treat day is a joke. A cause of this over-reach is also malevolent: the ever-increasing sense of urgency (becoming terror later) as the deadline looms, because ‘success’ is so important it erodes any objective sense of what is realistic or achievable. Which brings me to:

Something not even made yet is already a failure. On Kickstarter 56% of projects fail to make target and get zero. Unpack that stat and it’s pretty concerning: these creative people didn’t undertake Kickstarter lightly in the first place, they made a plan, shot a video, offered their fanbase all the bonuses in the world and still failed to hit target. That’s a whole lot of effort and commitment gone to define themselves as a big fat loser, for financial reasons rather than artistic judgement. I wonder what the damage done is, in real terms.

This is innately biased (of course) against inarticulate, disorganised and working class artists (whose wider communities and support bases tend to have fewer financial resources). I also reckon, although this is tenuous, that the system leans in favour of technically innovative, science-based, gimmicky, design or technical projects over pure art, because the former can be more easily explained, ahead of actually doing it.

New album releases go on forever. First the artist talks up the new album before even starting to make it. Then they endlessly document the process. Then it’s done and first they release it exclusively to funders. Then they do other posh formats separately, in order to send them out to other funders. Finally they release the album to everyone else. It’s been weeks since those first people got hold of it and someone immediately file-shared it. We’re bored now.

Finally, my biggest, most esoteric dissent speaks to broader issues about fundraising campaigns in general. These platforms rely on everyone turning a blind eye to a truth: that a very few devoted followers will fund almost everything. When artists draw resource from their audience, a very select core number of individual funders (relatively wealthy and truly devoted) will underwrite the whole ballgame. This is already true of the wider music industry: If we started analyzing the tiny contingency of people propping up our entire business, we’d be aghast. In crowd-funding, success or failure depends on whether the artist has those particular followers. I say this without specific data to back me up – however it is based on first hand experience not in the music world, nor business, but in the third sector (charity industry). In language and structure, arts crowd-funding campaigns far more closely resemble charity appeals than other kinds of business fundraising, right down to the ideas around ‘donating’ in return for special rewards. A charity industry ‘universal truth’ is that at least 80% of money comes from fewer than 20% of donors. Successful crowd-funding campaigns will always have exclusive, very high value rewards for much larger amounts, where ‘selling’ only a handful of them underwrites a massive proportion of the campaign. It’s an identical approach.

Honestly, so many artists I know who’ve crowd-funded would back me up here: because of this principle, the success or failure of a project is less down to the size of audience, or how hard the artist works the campaign across the breadth of their fan-base; it’s more down to whether they’re lucky enough to have a small core of very devoted and relatively wealthy fans, and/or some rewards of high value to offer those fans.

I believe, far too often, the artist becomes slave to the campaign, rather than the other way around. You would be astonished the number of artists out there who, even after publicly successful target-smashing campaigns, will later quietly express a range of regrets that they wouldn’t want their generous audience to know about. They look back and regret what they offered; regret the time wasted honoring those offers; regret how panicky they got about a ludicrous arbitrary definition of ‘success’; regret how the balance in their relationship with supporters shifted; regret not finding the funds elsewhere, so they could be more flexible about what it was they were making.

And these are the ones who won.

Now, I’m not really bothered; from all angles it’s just people making choices. I guess I just feel a bit sorry for them all, that they couldn’t try other ways first. And phew, I didn’t even mention Amanda Palmer.

ps. thanks to music fan and Words With Friends opponent Matt Rhodes for emailing me a question about recorded music pricing, which triggered this article – sorry I haven’t actually answered your questions at all, Matt, I’ll get to them.

I think I played my longest ever show last night, at Hebden Bridge Arts Festival.

Hebden Bridge (stunning little Yorkshire valley town in the Pennines, fierce non-conformist spirit, steep hills) is recovering from horrendous floods last week. It’s amazing the Arts Festival went ahead really; many businesses and cafés are still shut to clean themselves up. So for emergency venue logistics reasons, my gig in the brand new (not quite finished) Town Hall needed to run concurrently with an improvised dance performance downstairs (since my audience had to walk across their stage to get to me, or more importantly to the bar!).

So I was asked to do two sets, with the first one lasting at least 40 minutes, so both audiences would go for their interval drinks at the same time. Inevitably then my second set just stretched out – it ran well over an hour in the end, so total performance time works out at 1 hour 55 minutes.

I don’t know if this is a good or bad thing. Right now it feels great as an ‘achievement’ but obviously that has nothing to do with ‘ace’ or ‘shite’ gigs, really. The audience was proper lovely and (I’m sure) was honestly up for an encore, so that’s a good sign after 90 minutes I guess.

Mostly I’m pleased I can do that with songs to spare (for example as soon as I walked off I was annoyed for missing out ‘The Shape We’re In’) and I’m proud to say that although there was a bit of thinking beforehand about song running order, I didn’t use an actual setlist, instead mentally connected ‘chunks’ of different sets that work well together. 🙂

By the way, if you were there and have an opinion on the lengthy set – criticism is fine – do let me know.

Here’s the set, it’s 26 songs:

Love Is Not Rescue

A Box To Hide In

Open Books

Old Men

Bankrupt

A Plague On Both Your Houses

Preaching To The Converted

What If My Heart Never Heals?

Nintendo

Giraffes

7 Hearts

Stop Listening

(interval)

Open & Shut

Ankles

M1 Song

Shit From All Angles

Cull

The Huntsman Comes A-Marchin’

The Tin Man

Words Fail Me

Tall Woman

Elephant In The Room

The English Earth

(encore)

Lines & Squares (A.A. Milne)

Market Square (A.A. Milne)

Tomorrow Morning

Then I drove home to Brighton. Get me, with the stamina.

*EDIT* By the way, I forgot to say: on my last tour I opened and closed with two Milne poems; ‘Halfway Down’ and ‘Come Out With Me’ (which then reprises a verse of ‘Halfway Down’ at the very end). If you’re (by any chance) wondering why I didn’t do that – and why there are only two Milne poems in the set, just thrown in the encore – it’s because I also performed the full Disobedience A.A. Milne show at HBAF the previous day – and there were some people who came to both shows. So I wanted to minimise crossover. That’s also why I didn’t play ‘Hedgehog Song’ – it’s in the Milne show too.

Here is an exceptional resource, if you just started gigging and perform solo. Recently Tom Robinson ran this workshop for BBC Introducing and now he’s written up a full-length guide, in which he really digs deep into first steps of developing solo stagecraft.

FRESH ON THE NET: Gigging Solo

Obviously any guide like this is a template not a rule book. But I’ve simply never seen such a brilliant piece, that covers this much ground and includes so much good gigging sense.

I had four additional thoughts (read Tom first though):

1) When you’ve got your friends in…

If you have a room full of strangers but there’s a group of your mates somewhere down the front, it’s very tempting to aim your set at them, or even more riskily, get involved with in-jokes or banter, especially because they’ve come to support you. Resist this as much as possible: the first thing that happens when a performer focuses on friends is that the rest of us, not being part of that, feel left out. Think of it like this: your mates should be the last people you need to win over.

2) Refer to the audience in the singular as much as possible…

This ties in to what Tom says about saying “you” instead of “I” and in fact it’s a trick I learnt as a kid from Phillip Schofield back when he presented Children’s BBC in the broom cupboard with Gordon the Gopher: talk to your audience as if they’re one person. So: “It’s good to see you, thank you for coming,” is better than “It’s good to see so many of you, thank you all for coming,” as subconsciously each person feels directly addressed. You can’t always do it but it’s worth getting into the habit.

3) Have a few ‘stand-up’-style put downs in your pocket…

You will get heckled at some point. It may be cool, it may be nasty. The easiest solution is always to laugh and be nice in response but with a funny line, remembering you’re up onstage with the power of the microphone (and you can say you’re the one “getting paid” to be there, even if you’re not!). However you might want/need to get nastier and remind them what you did to their Mum or Dad last night. But again, be careful not to get caught up in banter. If you focus on one group or person too much, you leave out everyone else.

4) If the gig is very small, don’t be afraid to ditch the stage altogether…

If you’re playing acoustic guitar, in a tiny room holding, say, fewer than 40 people and you’ve got their attention, you may make more impact performing unplugged. People enjoy that extra closeness and somehow think of you as rebellious for eschewing the gear. It’s also still seen as a special talent (or ‘braver’) to play unplugged, where in truth it sounds a lot closer to your rehearsals at home and you can hear yourself better. Only works if the room’s quiet though.

Finally, the one part of Tom’s guide I find myself (mildly) disagreeing with, is when he discusses onstage monitoring. I’d argue that Tom’s own vocal power and experience means he doesn’t rely on monitoring as some singers do (me included). I personally would never ditch the monitors and rely on the PA, or ask for the FOH mix to be in the monitors. I also think it’s not so important to bring a sound engineer to small pub/club shows and can sometimes be detrimental: the house engineer who works at the venue is likely to do as good a job, since s/he already knows the room. And, especially if you’re a support act, it can piss off the house crew, if your engineer starts messing with the desk. Yes, you’ll occasionally find duff / moronic house engineers but gigging on a budget, how good really is the friend you’re bringing? I find it of more value to have someone smart with you for soundcheck, who simply knows how you should sound – but doesn’t want to play with the desk. Your friend can listen from the floor and give suggestions.

Anyway, that’s my 2p for now; even having done almost 2,000 shows myself over 15+ years, I found reading Tom’s piece useful and cringed at a couple of basic errors I still make. So I hugely recommend it.